Loading...

18th February 2019

Economics, especially monetary economics, has a tendency toward utopian fantasy. The latest utopian fantasy to emerge from monetarist economics goes by the name Modern Monetary Theory or MMT. It is worth paying attention to the debate around MMT because it could have important implications for financial markets.

Some advocates of MMT are using the theory to claim governments can spend without limit, and that they can do so without raising taxes. They can do this, according to MMT, because governments can print their own money. As a result, governments can safely accumulate an unlimited about of debt, because they can always print new money to pay off that debt. Unsurprisingly, some critics of these ideas have dubbed MMT a Magic Money Tree.

The current environment of political populism is providing a willing audience for learned economists willing to tell politicians it is safe to spend without limit. As a result, MMT is beginning to gain an audience amongst policymakers.

The current environment of political populism is providing a willing audience for learned economists willing to tell politicians it is safe to spend without limit. As a result, MMT is beginning to gain an audience amongst policymakers.

The idea underpinning MMT is both simple and true: sovereign countries that control their own monetary system can print an unlimited amount of their own currency.

It follows therefore, a government who controls its own monetary system, and who borrows only in its own currency, need never go bankrupt. If its debts become too burdensome it can simply print the money to pay them off. If the government wishes to spend more it can simply print the necessary money. What’s more, because the spending can be funded with printed money it is unnecessary to raise taxes to match the higher spending.

This line of reasoning leads advocates of MMT to conclude that governments can and should fund any and all worthy causes ranging from infrastructure investment to social security and healthcare costs.

Hopefully by now MMT is sounding too good to be true, that is because it is too good to be true.

Although governments can print themselves unlimited money, they cannot turn that newly printed money into productive real economic activity.

A simple thought experiment helps explain what is likely to happen if a government chooses to print itself more money and then spend that money.

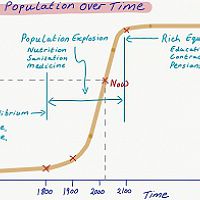

Because economic activity is a relatively slowly moving variable, we can assume the real economy – the amount of goods and services being manufactured and sold – remains roughly constant through the money printing exercise. As a result, when a government awards itself more spending power, through the printing press, it will be able to buy a greater share of the country’s economic output. This will leave a smaller share of economic output available for the private sector. In other words, the purchasing power of the money held by the private sector will fall. This is of course is what we mean by inflation – rising prices or equivalently a falling value of money.

Looking at the money printing process in this way is helpful because it makes the connection between money printing and taxation clear. A government may gain spending power by taxing its citizens, which reduces the citizens’ spending power, or by printing its own money, which also reduces citizens’ spending power in the same way. It would therefore appear that Government spending through monetisation and through taxation are equivalent. There is no free lunch and there is no Magic Money Tree.

In practice, however, there are some important political differences between a government funding itself through taxation and one funding itself though the printing press. A government funded through taxation will find its spending plans closely scrutinised by a population, quite rightly, resistant to excessive taxation. By contrast a government funding itself through the printing press appears to be giving without taking. Monetised spending is popular, even populist, and usually occurs without scrutiny.

It is the lack of oversight that accompanies monetised government spending that is especially dangerous. History has shown us once a government begins funding itself through the printing press the process often spirals out of control, leading to an inflationary spiral.

The inflationary spiral then tends to damage economic activity leading to a contraction in the real economy. As a result citizens find themselves suffering a falling share of a contracting economy. Zimbabwe is a recent example of such a monetised economic collapse, Venezuela a current example and Turkey a potential example.

To be fair to the more moderate faculty of the MMT school, some proponents of MMT recognise the inflationary dangers associated with monetised spending. This group tend to argue governments can and should increase spending but only up to the point at which inflation starts to become problematic. Though theoretically appealing this approach carries significant dangers.

The key difference between MMT and Keynesian stimulus appears to be that Keynesian policies are seen, in theory, as temporary counter cyclical measures whereas the proponents of MMT appear to be arguing for permanent stimulus on a much larger scale. Given the lags in the relationship between recorded inflation and monetised spending and the difficulty in reversing spending plans once enacted, it is hard to see how the MMT mindset, if adopted by policymakers, will not inevitably lead to an inflationary cycle.

For investors the most obvious consequence of MMT would be a significant reduction in the real spending power of money. Money would become worth less and in extremis literally worthless. Investors holding cash or nominal bond portfolios would likely suffer the greatest losses in real terms while those real assets would likely fare much better.

To be clear, we don’t see the inflation risk posed by MMT as an imminent threat. But populism is on the rise and historically populist leaderships have proven especially susceptible to monetary snake oil. We have been surprised by increasing commentary around MMT and the degree to which it is being taken seriously.

We will be keeping a close eye on the MMT debate and advise others do the same.

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

Can fair fees make active managers more sustainable?

2

Can fair fees make active managers more sustainable?

2

Facts not Opinions

2

Facts not Opinions

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Regulating Psychopaths

2

Regulating Psychopaths

2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

Reckless Prudence - How to break a pension system

2

Reckless Prudence - How to break a pension system

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Captain Kirk and the science of economics

2

Captain Kirk and the science of economics

2

Meerkats and Market Behaviour - Thoughts on October's stock market fall

2

Meerkats and Market Behaviour - Thoughts on October's stock market fall

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2