Loading...

5th April 2023

March has been an eventful month for the global financial system, it may yet be seen as marking an important regime change in the global financial system.

On the 19th Credit Suisse, which had been failing gradually for some time, was handed to its rival UBS in a shotgun marriage, arranged by the Swiss regulator. This was preceded by the failure of three U.S. banks, Silvergate Bank on the 8th, Silicon Valley Bank on the 10th and Signature bank on the 12th, all three of which failed rather suddenly. While this mini banking crisis was unfolding, another, possibly more important, drama was taking shape. On the 2nd China announced it was preparing to purchase oil in its domestic currency the Yuan, rather than in U.S. dollars. This announcement was followed, first on the 15th, by confirmation that Saudi Aramco would sell oil to China in Yuan and then, on the 31st, that TotalEnergies would also supply LNG in Yuan.

The implications of Saudi Arabia, traditionally a staunch ally of the U.S., being willing to accept Yuan rather than USD for its oil is noteworthy in itself, but doing so immediately after the March 10th announcement of China having brokered a resumption of diplomatic relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran, is suggestive of tectonic shifts in the geopolitical landscape. As if to underline the new closer relationship Saudi Arabia and China, on March 27th Saudi Aramco announced two new investments in the Chinese oil refining industry. In addition, on March 21st President Xi made a high profile visit to see President Putin in Moscow to discuss, amongst other things, brokering a peace deal between Russia and Ukraine. The statecraft around that visit was clearly designed to project an image of close cooperation between Russia and China. Then on April 2nd, OPEC+ announced a surprise series of production cuts aimed at boosting the price of oil. Tellingly these cuts were led by both Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Taken together, these events suggest a significant degree of policy coordination between China, Saudi Arabia and Russia which, if it persists, would represent a significant realignment of international relations and a clear step away from and international trade system almost exclusively dominated by the USD.

Naturally any challenge to the pre-eminence of the USD in trade also leads to questions over its status as the primary reserve currency and therefore its value versus other currencies and commodities. Tellingly gold traded above $2000 an ounce three times in March and has again moved above that level in early April.

Both the banking crisis and these nascent threats to USD hegemony may quickly fade; the demise of the dollar has been prematurely forecast many times before. That said, given the participants involved, it would be unwise to dismiss these geopolitical events out of hand and the added complications of a fragile domestic banking system may hinder policymakers’ response.

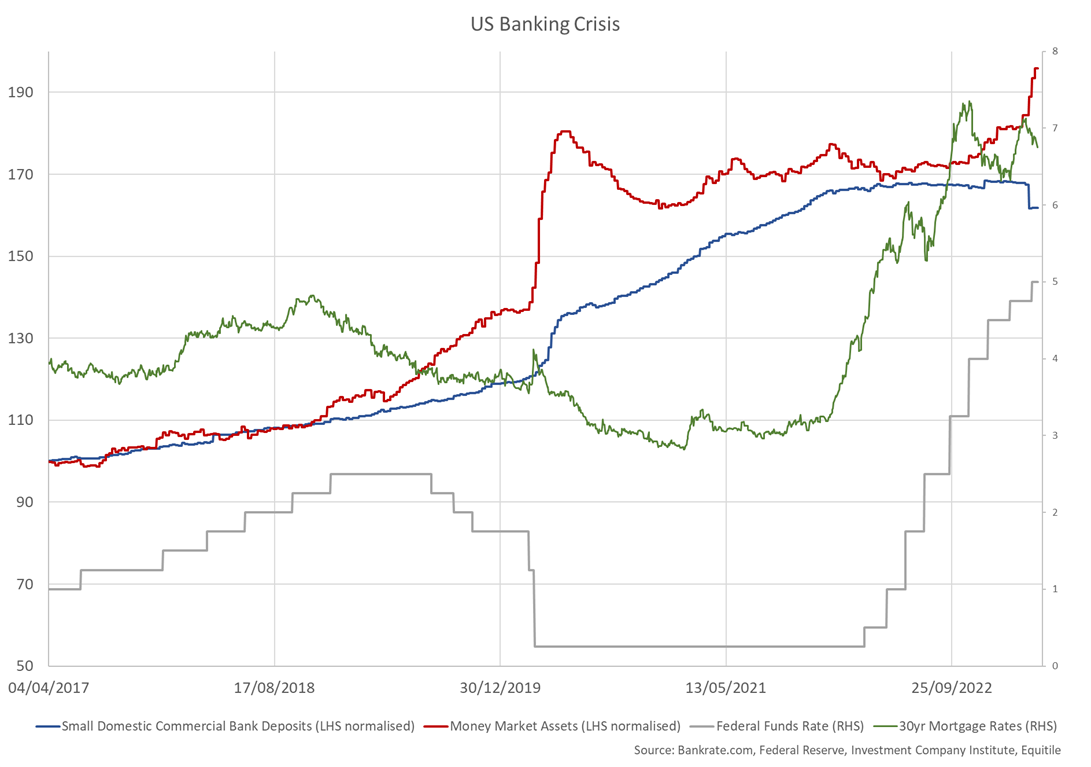

Of the four bank failures we are inclined to view Credit Suisse’s problems as idiosyncratic to that institution and therefore of lesser systemic importance. By contrast the failures of the three U.S. banks, and weakness of many others, appears to be connected by a common process within the US capital markets. As far as we can tell this process is still operating suggesting systemic risks may still be building. The source of the problems can be explained with reference to Figure 1. which shows the evolution of the Fed Funds Rate (grey), regional bank deposits (blue), money market assets (red) and US mortgage rates (green).

Consider first the period in early 2020 when, in response to the economic dislocations caused by Covid lockdown policies, the Federal Reserve cut interest rates to essentially zero and in partnership with the government engineered a substantial fiscal and monetary stimulus. The stimulus, at that time, is evident by the sudden surge in both bank deposits (blue) and money market deposits (red).

This sudden infusion of cash into the banking system occurred during lockdown when loan demand was generally weak. As a result, many banks appear to have invested significant portions of those deposits in the US mortgage bond market. During that lockdown period the prevailing 30 year US mortgage rate was approximately 3% (green).

As lockdown was eased in late 2021 and early 2022 those accumulated cash balances were suddenly released into the economy in the form of a burst of pent-up demand, which met with a still recovering supply side hampered with significant logistical constraints. As a result, inflation surged as excess money chased a shortage of goods and services. In response to this surging inflation the Federal reserve began aggressively raising interest rates from Q2 2022 onwards.

Money market funds, which are generally constrained to investing their deposits in short-dated bonds were quickly able to offer the new higher interest rates to their depositors. By contrast some of the banks, who had invested their deposits in long maturity bonds, at the lower rates prevailing in 2021, were faced with capital losses on their investment portfolio and were therefore unable to pass on the higher rates to their customers. As a consequence, deposit growth (blue) first stalled from mid-2022 and then more recently moved into reverse as customers shifted cash into higher yielding money market funds (red).

The latest data suggests money market fund assets are still rising and regional bank deposits are still contracting. Moreover, bank customers are now aware of the fragility in the banking system and the question of to what degree their bank deposits are guaranteed or not. For these reasons, as far as we can see, the forces causing a reallocation of funds out of banks and into money market funds remain in place. It would therefore seem premature to conclude the U.S. banking crisis is already over. In our view, the danger will only pass once either the banks’ investment portfolios have matured, which will likely take several years, or once the Federal reserve begins reducing the gap between prevailing money market rates and what the banks can afford to pay. In other words, we believe, the regional banking system needs significant interest rate cuts and quickly.

Figure 1.

On the other hand, inflation remains high and may be about to get another boost from resurgent oil prices, all of which maintains pressure on the Federal Reserve to continue raising or at least holding interest rates at current levels.

In short, we worry the Federal reserve, by first facilitating excessive stimulus in 2020 and then by trying to drain that stimulus too rapidly in 2022, has caught itself in a trap of its own making. From here it can either stabilise the banking system with lower rates or stabilise the price level with higher interest rates, it is difficult to see how it achieves both at the same time.

With these powerful countervailing forces acting on monetary policy it is unusually difficult to anticipate the near-term policy steps. However, in the medium term we suspect policymakers will take the well-trodden path of least resistance, that being to lower interest rates to shore up the banking system and suffer whatever inflationary consequences that policy causes. If they are lucky, they may have already achieved enough demand destruction to bring overall inflation lower, even with the new higher oil prices. This would allow them to reduce rates into a slowing economy. If they are unlucky, they may be forced either to reduce rates while inflation remains elevated or may instead hold rates up until a bigger financial crisis emerges to force their hand.

The pressure to monetise away the enormous cost of lockdown is building which, along with emerging geopolitical shifts, might well lead to some of the reserve currency status, which the US has enjoyed for many decades, being called into question. We are watching gold, oil and commodities closely, to our eye they are already hinting at a replay of a 1970’s style stagflation scenario.

***

To join our distribution list, please send ‘subscribe’ to: info@Equitile.com

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

Lockdown: What did we get? Why did we do it?

2

Lockdown: What did we get? Why did we do it?

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Modern Monetary Theory - The Magic Money Tree

2

Modern Monetary Theory - The Magic Money Tree

2

Jubilee - A time for borrowers to celebrate?

2

Jubilee - A time for borrowers to celebrate?

2

0

0

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Artificial Intelligence - Scary Good

2

Artificial Intelligence - Scary Good

2

When Science Fails

2

When Science Fails

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Reckless Prudence - How to break a pension system

2

Reckless Prudence - How to break a pension system

2

Public Deficits, Private Profits

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2

Public Deficits, Private Profits

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2