Loading...

14th July 2021

“The cost of being a responsible citizen was just too great.”

Liaquat Ahamed, Lords of Finance

In a world where social norms are being torn up, it is reassuring to see some traditions remain steadfast. I am, of course, talking about England losing on penalties in a major football tournament. Traditionally, the German team is tasked with dealing the knockout blow, but this week the job fell to the Italians. We offer Italy our warm congratulations and hope we don’t have another half century to wait for the next penalty shoot-out in a major final.

In a world where social norms are being torn up, it is reassuring to see some traditions remain steadfast. I am, of course, talking about England losing on penalties in a major football tournament. Traditionally, the German team is tasked with dealing the knockout blow, but this week the job fell to the Italians. We offer Italy our warm congratulations and hope we don’t have another half century to wait for the next penalty shoot-out in a major final.

Strange as it may seem, the European cup final was not Europe’s most important event in July. Of far greater importance was a little noticed statement issued by the European Central Bank’s (ECB) governing council announcing their new monetary policy strategy. We expect it will take years for the full significance of the ECB’s new policy to become clear, but when it does, we believe it will be seen as a landmark event in the history of ECB, the single currency and by implication the European Union itself.

If our interpretation is correct, the ECB statement marks a break with the hard-currency traditions of the German Bundesbank and a move toward the more ‘flexible’ monetary strategies associated with Southern European countries in the period before the launch of the Euro. In other words, both football and monetary policy are going Rome.

Part of the policy announcement is a welcome change to the wording of the ECB’s official inflation target. Previously, the target was ‘close to, but below 2% inflation per year’ now it is a much simpler ‘2% inflation target over the medium term’. This change clears up the ambiguity and deflationary bias of the previous wording where 2% was a hard annual upper bound but there was no clear lower bound. The new statement also makes clear the target is over the ‘medium term’. This we take as adopting what has been described as the ‘makeup strategy’, whereby the central bank should address periods of inflationary undershoot by seeking to engineer matching periods of inflationary overshoot, and vice-versa, to achieve a 2% inflation rate averaged over multiple years. This framework isn’t new, it mirrors what is already being practiced in the US.

Arguably, the deflationary bias embedded in the ECB’s previous asymmetric target helped contribute to the low Eurozone inflation of the last decade, which has averaged just 1.2%. Interestingly, this undershoot leaves current prices approximately 9% lower than they would have been had the ECB achieved its new target.

Another key detail of the statement involves the observation that real interest rates have fallen:

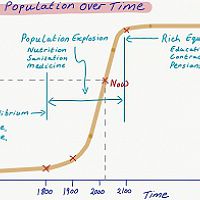

“the global economy have been undergoing profound structural changes. Declining trend growth, which can be linked to slower productivity growth and demographic factors, and the legacy of the global financial crisis have driven down equilibrium real interest rates…”

The decline of real interest rates is objectively true. That said, the degree to which this decline is due to slower productivity growth and demographic factors is debatable. Attributing low real interest rates to these factors is useful for the ECB, as it positions the cause as exogenous to monetary policy. However, a credible case can be made that the expansion of credit over recent decades has itself caused the lowering of equilibrium real interest rates. The logic behind this argument is straightforward; as the debt stock rises the real interest rate burden must fall in order to keep the burden of interest payments manageable.

This reasoning is akin to elements of Hyman Minsky’s financial instability hypothesis whereby self-reinforcing cycles of indebtedness can emerge endogenously within an economy. Rising indebtedness beget lower interest rates which in turn facilitate more borrowing, requiring even lower interest rates. In light of this concern, it is interesting to note the ECB suggesting interest rates may no longer be up to the job of controlling monetary policy:

“…This has reduced the scope for the European Central Bank (ECB) and other central banks to achieve their objectives by exclusively relying on changes in policy interest rates.”

In our view, the ECB has already lowered interest rates beyond the point where they start to undermine, rather than support, economic activity. In this respect we welcome the statement and hope that it means the ECB does not intend pushing interest rates even further into negative territory.

If interest rate policy has run out of road, other policy tools must now assume the central role of monetary policy. We take this to mean quantitative easing should now be viewed as normal monetary policy.

At the outset, quantitative easing was presented as a short-term mechanism to control interest rates, in the financial markets, through temporary bond purchases. However, those purchases now look far from temporary and quantitative easing has seemingly morphed into outright monetisation, whereby the central bank supplements government tax receipts with printed money, in order to maintain fiscal stimulus. This is essentially the policy prescription advocated by Modern Monetary Theory.

Our concern– pardon, one of our many concerns – with this policy is, as explained, it has an addictive quality as it becomes difficult to either withdraw the ongoing monetisation or raise interest rates without triggering a recession, which would push up real interest costs to intolerable levels.

The logical alternate exit from this situation is to pursue a long-term policy of financial repression whereby the real value of the accumulated debt stock is reduced by holding nominal interest rates below prevailing inflation rates. In our view, the ECB’s statement is laying the ground-work for just such a strategy.

The change to the framework allows the room to overshoot the inflation target for an extended period and the normalisation of non-interest rate policy tools allows the ECB to suppress bond market rates through asset purchases.

“To maintain the symmetry of its inflation target, the Governing Council recognises the importance of taking into account the implications of the effective lower bound. In particular, when the economy is close to the lower bound, this requires especially forceful or persistent monetary policy measures to avoid negative deviations from the inflation target becoming entrenched. This may also imply a transitory period in which inflation is moderately above target.”

Finally, we would note the broadening of ECB’s policy goals to include full employment, social progress and environmental improvements. The bundling of these important issues into the monetary policy framework has occurred largely without discussion or debate as to their appropriateness or likely effectiveness. Nevertheless, the bundling has happened and represents a powerful narrative in support of a further loosening of monetary policy. If printing more money means a better environment, more social progress and full employment, who could say no?

“Without prejudice to the price stability objective, the Eurosystem shall support the general economic policies in the EU with a view to contributing to the achievement of the Union’s objectives as laid down in Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union. These objectives include balanced economic growth, a highly competitive social market economy aiming at full employment and social progress, and a high level of protection and improvement of the quality of the environment.”

"Climate change has profound implications for price stability through its impact on the structure and cyclical dynamics of the economy and the financial system. Addressing climate change is a global challenge and a policy priority for the EU. Within its mandate, the Governing Council is committed to ensuring that the Eurosystem fully takes into account, in line with the EU’s climate goals and objectives, the implications of climate change and the carbon transition for monetary policy and central banking. Accordingly, the Governing Council has committed to an ambitious climate-related action plan. In addition to the comprehensive incorporation of climate factors in its monetary policy assessments, the Governing Council will adapt the design of its monetary policy operational framework in relation to disclosures, risk assessment, corporate sector asset purchases and the collateral framework."

We are less than convinced looser monetary policy will deliver these goals, but we are reasonably convinced policy makers are going to help us find out.

To join our distribution list send ‘subscribe’ to: info@Equitile.com

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Meerkats and Market Behaviour - Thoughts on October's stock market fall

2

Meerkats and Market Behaviour - Thoughts on October's stock market fall

2

Seductive Charm

2

Seductive Charm

2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Revolutionary Fervour

2

Revolutionary Fervour

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

Lockdown: What did we get? Why did we do it?

2

Lockdown: What did we get? Why did we do it?

2

Is corporate debt addictive?

2

Is corporate debt addictive?

2

Monetary Policy on a War Footing

2

Monetary Policy on a War Footing

2

Undoing the Mistakes of QE

2

Undoing the Mistakes of QE

2

Over Easy - Can Monetary Policy Become Self-Defeating?

2

Over Easy - Can Monetary Policy Become Self-Defeating?

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

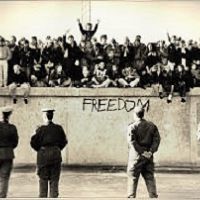

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

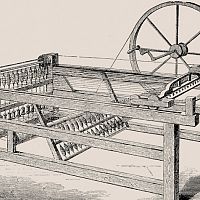

Luddites and the New Social Revolution

2

Luddites and the New Social Revolution

2

Facts not Opinions

2

Facts not Opinions

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

Lumbering corporate dinosaurs face mass extinction

2

Lumbering corporate dinosaurs face mass extinction

2

0

0

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Public Deficits, Private Profits

2

Public Deficits, Private Profits

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

Regulating Psychopaths

2

Regulating Psychopaths

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

A creditable recovery

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2

A creditable recovery

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2