Loading...

13th June 2022

In his recent speech announcing a £15bn spending package to tackle the cost-of-living crisis, UK Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, confidently professed to parliament that “We have the tools and the determination we need to combat and reduce inflation”. Although there was talk of fiscal prudence and supply side reforms, and a windfall tax on energy companies, the main thrust of his plan was to make direct transfers to help families out with energy bills and council tax.

In his recent speech announcing a £15bn spending package to tackle the cost-of-living crisis, UK Chancellor, Rishi Sunak, confidently professed to parliament that “We have the tools and the determination we need to combat and reduce inflation”. Although there was talk of fiscal prudence and supply side reforms, and a windfall tax on energy companies, the main thrust of his plan was to make direct transfers to help families out with energy bills and council tax.

It's not the first time a Conservative Chancellor has faced accelerating inflation and reacted with more government spending. Anthony Barber, who described stagflation as “a new and baffling combination of evils”, had already overseen a rapid rise in inflation which, having been less than five percent for most of the 1960s, was touching ten percent by the time of his infamous 1972 “Dash-for-Growth” Budget. Like Sunak, he saw more government spending as the solution to a stagflationary spiral and, unperturbed by a burgeoning budget deficit, he did not believe that his stimulus to demand was “inimical to the fight against inflation”. He was wrong of course; two years later, UK inflation was over twenty percent - albeit with an oil crisis to spur it on.

It took a dire situation to open the political establishment’s mind to the simple message of Keith Joseph’s 1974 Preston speech - Inflation is Caused by Governments. Joseph upended cross-party orthodoxy in UK politics with the assertion that inflation was a self-inflicted wound, the result of “trying to do too much, too quickly” or, more specifically, “the creation of new money – and the consequent deficit financing – out of proportion to the additional goods and services available”.

Having previously presided over the Department of Health and Social Security, with the largest bureaucracy of any government department, he understood first-hand how successive governments had, in his words, “gone astray”. The ratchet effect which led to ever-higher government spending had, by 1974, led to economic instability not seen since the Second World War. In his words;

“all other social and economic objectives will be lost unless inflation is abated. Growth, social peace, full employment, regional balance, social services – no one of these aims can be sustained if inflation is allowed to continue at its present or anything like its present pace”.

In the run up to the 1974 stagflation and the demise of the ‘Barber Boom’, it was the spectre of thirties-style mass unemployment which led successive governments to persistently spend their way out of problems, even before it was truly manifest. As Joseph pointed out, however, “There never was serious unemployment since the war on anything remotely like the scale or conditions of the 1930s”. This fearful sentiment, however, remained at the heart of the ratchet effect driving government spending.

What insight does Joseph’s Preston speech offer on the inflation we see today and how it should be dealt with?

As in 1972, we are witnessing surging commodity and energy prices. Primary product prices were rising sharply before the Yom Kippur war of 1973, eleven months before Joseph’s speech, but the OPEC crisis seriously compounded that problem. Similarly, the Ukraine crisis has hit as energy markets were already tightening for structural reasons – this time under-investment in fossil fuel rather than the growing power of OPEC.

Although Joseph acknowledged that the rise in world prices in the early seventies created inflationary pressure, it was the reaction of governments, he thought, that did most damage and the inflation it engendered was much more menacing.

Commodity prices won’t keep rising forever and it is possible that in today’s capital light, dematerialized world they don’t play as large a role as they once did. In the end, conflicts end, and new production capacity will be brought on-stream to moderate price tension. Inflation caused by governments doesn’t self-correct, though, it requires a shift in policy.

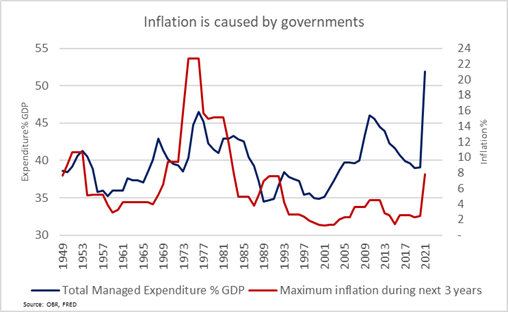

Once again, the UK finds itself with government spending at historic highs relative to GDP. The accompanying chart shows UK government spending relative to GDP against the highest inflation rates in the ensuing three years – higher inflation follows higher spending. (Note this shows spending up to 2020 which includes that related to Covid lockdowns. Spending is still expected to be more than 45% of GDP until 2023, as it was at the time of the Preston speech)

Once again, the UK finds itself with government spending at historic highs relative to GDP. The accompanying chart shows UK government spending relative to GDP against the highest inflation rates in the ensuing three years – higher inflation follows higher spending. (Note this shows spending up to 2020 which includes that related to Covid lockdowns. Spending is still expected to be more than 45% of GDP until 2023, as it was at the time of the Preston speech)

The latter-day version of trying to do too much, too quickly is, in a way, more troubling than it was in the seventies. Not only are governments, especially the UK government, taking responsibility for an ever-growing portion of economic activity, they are in many cases trying to shrink economic activity in the private sector. COVID lockdowns - the first policy in history aimed at deliberately stopping economic activity on a grand scale - were an extreme example of this, but the accelerating impact of the green agenda will, over time, prove to be equally destructive to large parts of the private economy. A government doing too much, too quickly while reducing the number of goods and services available from the private sector is actually more inflationary than the dynamics which Joseph described.

None of this is to say that government policy isn’t borne out of good intentions. Once again from the Preston speech in 1974;

“Government after government chose to take the risk, for several - in themselves not ignoble – reasons. The assumptions were probably always the same; that the inflation would only be mild; that it could be stopped; and above all, that mild inflation seemed a painless way of maintaining full employment, encouraging growth, and expanding the social services…… Thus, excessive injections of money, undertaken by intelligent and enlightened men with good intentions, have wrought great havoc in our economy and society”

There’s always a theoretical justification for government action. Today we have Modern Monetary Theory, but as Joseph observed, in the seventies there was no shortage of experts to justify state expansion.

“Influential groups in Whitehall, Cambridge and the National Institute of Economic and Social Research seem to deny the proposition that rapid money supply growth leads to inflation”

In summary, as in the seventies, governments are trying to mitigate the adverse impact of exogenous and self-inflicted phenomenon through monetary expansion, deficit financing and the relentless expansion of the state’s role in the economy.

As in the seventies, one particularly troubling aspect of state expansion is exponential growth in regulation.

“Over and above the budget damage, industry has been having to put up with the anti-business, anti-profit attitudes of Ministers and the threat of state grab and state interference to every large firm…. by extending ever since the war government intervention we have politicised our economy. A result is that longer-term considerations have since the war often been subordinated to short-term political convenience”

The expansion of government doesn’t simply crowd out private sector activity in a way that we are taught in first year of university. The concurrent rise of the regulatory state crowds out endeavour, innovation and the very competition which drives individuals and companies to be more efficient, more productive, and simply better. Private sector competition is naturally deflationary. Firms, when left to their own devices, generally out-compete each other to provide better goods and services ever more cheaply. If government hinders that process through excessive and complex regulation, it will find it harder to tackle inflation itself.

There are now over 90 regulatory bodies in the UK, many at arms-length from more democratically accountable government. The civil service, in terms of headcount, has increased by 24% since 2016. Moreover, the motives behind regulation morphed in recent decades from the promotion of stability, fairness, and safety to also encourage a change of behaviour amongst the population to be in line with incumbent political and social agendas. Of the 91,000 civil servants added to the public payroll since 2016, by far the largest group, nearly 12,000, are working in policy creation[i].

Although it seems the current UK government’s default is a Barber-Style response to crises, dissenting voices are now getting louder in political circles with respect to the size of the state and its role in economic life. The government itself is now looking to cut the number of civil servants back to 2016 levels, and some of the more influential think-tanks are starting to contemplate the scale of the regulatory issue[ii].

Keith Joseph’s Preston speech fired the starting gun on an economic revolution that would prove to be as contentious as it was disruptive. It will take an unusual politician by today’s standards, however, to deliver its modern equivalent. For Joseph’s message came with an implicit admission that we rarely hear from politicians today – culpability. He began by accepting his “full share of the collective responsibility” in creating the environment the UK then faced.

Investment Implications

The US equity market bottomed, in nominal terms at least, the month of Keith Joseph’s Preston speech, the UK equity market bottomed two months later.

Investors had of course experienced a brutal loss of value in the preceding two years. £100 invested in the UK market at the end of 1972 was worth just £27, inflation adjusted, by the end-of 1974. There were many things about 1972-74 that suggest the environment was worse than it is today. The UK economy was more sensitive to the oil price and industrial unrest was rife, in what was a much more industrialised economy. Moreover, the UK had only recently given up on pegging the pound to the US dollar and a commercial real estate bubble was bursting, which itself lead to a secondary banking crisis.

The US was less bad, $100 invested at the end of 1972 in the US equity market was worth around $50 in real terms by the time the market bottomed.

From the bottom in 1974, however, the experience of investors was pretty good. Investors in the UK doubled the real value of their remaining investment in 1975 and by the end of the 1970s they were back at £61 in real terms, still some way off their investment at the top in 1972 but recouping most losses had they been building up investments in preceding years.

Most interestingly, once the policies that Joseph prescribed in his 1974 speech began to be enacted – he was made Head of Policy under Thatcher – investors did extremely well. The £100 they invested at the top in 1972 would be worth £261 in real terms by the end of 1989, and that’s with the crash of ’87 in between. Investors in the US had a similar experience, with Reagan in the White House and Paul Volcker in the Federal Reserve – investors in the US equity market had a near 14% real return on average during Volcker’s tenure.

Market consensus has settled on the simple notion that asset prices can only increase as monetary policy eases. What the experience of the seventies and eighties taught us, however, was that stock market investors, in the final analysis, prefer their governments and central bankers to facilitate a healthy economy. One that is dynamic, innovative and productive. It makes sense, therefore, that if a deficit of growth is a problem, then the markets like central banks to be dovish and governments to be fiscally supportive, as in recent years. If inflation and state over-reach is the problem, however, stock market investors should, over time, prefer those problems to be dealt with instead.

***

To join our distribution list, please send ‘subscribe’ to: info@Equitile.com

Seductive Charm

2

Seductive Charm

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Luddites and the New Social Revolution

2

Luddites and the New Social Revolution

2

Reckless Prudence - How to break a pension system

2

Reckless Prudence - How to break a pension system

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

Revolutionary Fervour

2

Revolutionary Fervour

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Investment Letter - Eternal Adaptation

2

Investment Letter - Eternal Adaptation

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Hanging the Wrong Contract?

2

Hanging the Wrong Contract?

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

Debt & the magical mathematics of Brahmagupta

2

Debt & the magical mathematics of Brahmagupta

2

Jubilee - A time for borrowers to celebrate?

2

Jubilee - A time for borrowers to celebrate?

2

Lumbering corporate dinosaurs face mass extinction

2

Lumbering corporate dinosaurs face mass extinction

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

When Prophecy Fails - How to ignore doomsday forecasts

2

When Prophecy Fails - How to ignore doomsday forecasts

2

0

0

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

When Science Fails

2

When Science Fails

2

In Search of Stability & Growth - If only Europe was more like the US

2

In Search of Stability & Growth - If only Europe was more like the US

2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Facts not Opinions

2

Facts not Opinions

2

Over Easy - Can Monetary Policy Become Self-Defeating?

2

Over Easy - Can Monetary Policy Become Self-Defeating?

2

Barney's P Curve - Why we expect higher inflation

2

Barney's P Curve - Why we expect higher inflation

2

Is it time to rethink monetary policy?

2

Is it time to rethink monetary policy?

2

Norway Moves to America - Mean reversion and industrial revolutions

2

Norway Moves to America - Mean reversion and industrial revolutions

2

Captain Kirk and the science of economics

2

Captain Kirk and the science of economics

2

Build a company on prudence and trust, not debt

2

Build a company on prudence and trust, not debt

2

Public Deficits, Private Profits

2

Public Deficits, Private Profits

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

Regulating Psychopaths

2

Regulating Psychopaths

2

Modern Monetary Theory - The Magic Money Tree

2

Modern Monetary Theory - The Magic Money Tree

2

Stock market superstars and the danger of a buy-and-hold investment strategy

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2

Stock market superstars and the danger of a buy-and-hold investment strategy

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2