Loading...

18th July 2016

The dangers of excessive debt are ever-present but the last few years have brought them into sharp relief. Eight years on from the Global Financial Crisis and with interest rates at historically low levels there’s still plenty of distress around. From the recent demise of UK retailer BHS, to the woes of Italian banks; from the collapsing shares of pharmaceutical giant Valeant to the stumbling debt crisis in Greece - there’s no shortage of case studies in imprudence gone wrong.

Despite these warnings, the nature of modern finance is such that companies increasingly favour debt finance ahead of equity. Moreover, while they once borrowed money to fund long-term investments, the return on which rendered the debt self-liquidating, leverage today fulfils a wholly different purpose. Balance sheet “efficiency” has become the holy grail for finance directors.

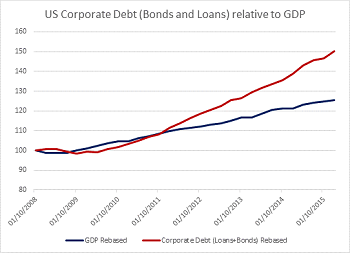

As interest rates relentlessly fall, debt levels continue to rise. At the turn of the century global corporate debt according to McKinsey amounted to $26trillion, just before the crisis it was $38trillion and by 2014 it had reached $56trillion. Much of that increase was in emerging markets, particularly China, but recently companies in the US have been re-leveraging too. Figure 1. shows how US non-financial corporate debt, both bank borrowing and bonds, has been increasing above GDP growth since 2007.

Data source. Federal Reserve of St.Louis

According to incumbent financial theory this is the best of all possible worlds. Companies are naturally trading-off the costs of debt finance, tax adjusted, against the costs they might incur if they go bankrupt. They are simply finding the optimal funding mix between debt and equity. Intriguing new thinking, however, is challenging this conclusion. It turns out that companies might not be optimising at all – they might instead be addicted to debt.

Experts have not had a great time of late. As George Cooper pointed out in his recent Constant Reformation letter, Brexit looks like one of those moments when dominant schools of thought are challenged; a time when the experts usually become intransigent, dogmatic and unwilling to criticise their own ideas. As the theories that have defined modern finance increasingly appear to be in crisis, however, the investment team at Equitile isn’t giving up on experts altogether. Intellectual rigour in academia is often more robust than elsewhere and academic theories can change behaviour in the real world – indeed it was Nobel prize winners of the last century that defined finance in this one. It’s always worthwhile to figure out which of the experts might be right and how their theories might challenge our current understanding.

One team of financial scholars have caught our eye of late. Professors Anat Admati, Paul Pfleiderer and Peter De Marzo at the Stanford Graduate Business School*, along with Martin Hellwig from the Max Planck Institute, look like they might overturn much of the incumbent thinking on debt. Disputing the standard models which assume leverage decisions are a simple trade-off, their work shows how debt becomes addictive. Once companies start to take on debt, they argue, the urge to take on more becomes irresistible; there is what they call a leverage ratchet effect.

They identified the phenomenon most clearly in the banks - Admati and Hellwig's book The Bankers’ New Clothes attracted much attention - but it exists, according to their thesis, in all companies.

The underlying causes of the ratchet effect are complex but they stem from a basic conflict of interest between shareholders and creditors. In essence, once a company has some debt, shareholders generally refuse to accept deleveraging and encourage companies to take on more debt whenever they have the opportunity. If a company proposes to reduce leverage through a bond buy-back, for example, the bondholders realise the deleveraged company would be less risky and demand a price premium for the bonds before selling them. In the final analysis it’s the bond-holders that extract all the value from the de-risking and shareholders, who pay upfront to deleverage the company, extract none of the incremental value. They don’t, as a consequence, support the bond buy-back.

The leverage ratchet effect applies to any form of deleveraging; retained earnings, rights issues, asset sales; all fall victim to the same problem – shareholders are incentivised not to accept them. There’s also a great irony. According to the Stanford model, shareholders even resist debt reduction when it leads to large gains in the value of the firm overall - debt becomes addictive no matter how destructive it becomes. Like a modern form of Gresham’s law, bad financing drives out good.

Existing theories of optimal capital structure, mainly derived from Modigliani and Miller’s seminal work in 1958, have an apparent mathematical completeness too powerful for corporate financiers to ignore. Admati and her colleagues’ thesis comes with the same mathematical rigour but draws a different conclusion. Moreover, it is dynamic. It looks at corporate finance decisions through time and not just as one-off independent decisions – a crucial differentiator which explains why the more indebted a company is, the more additional debt it wants to take on.

Many academics have challenged the basic tenets of modern finance – our own investment process is designed to overcome some of the challenges highlighted by behavioural finance for example – but the Stanford model is interesting because it doesn’t. It simply takes those theories further and draws a different conclusion. They haven’t just written off traditional financial theory as irrelevant – they’ve parked their tank on its lawn.

The implications are manifold. On a basic level it should make investors wary of any company that justifies high debt levels as mere balance sheet efficiency. But there are ramifications for policy too. The Stanford team’s work shows how the tax deductibility of corporate interest expenses - common to most countries - accentuates the problem. This is additional grist to an argument I made in Prospect Magazine last year where I called for a change in corporate tax policy in favour of equity finance.

The leverage ratchet also compounds a problem highlighted by fellow financial theorist Stewart Myers as far back as 1977. The so-called debt overhang problem makes companies reluctant to invest in worthwhile new projects as the value of those projects, once again, flows to creditors rather than equity holders. If successful investments make a company’s debt more secure and the ratchet ensures the value of that security accrues to bondholders, then shareholders become even more reluctant to finance them. Investment spending in the US has been lack-lustre since the financial crisis and, although there are myriad of potential causes, the debt ratchet in combination with the debt overhang problem looks like one of them.

At Equitile we avoid investing in companies with excessive leverage wherever we can and, in addition to looking at existing debt levels, we look for covenants that make excessive leverage difficult. But most of all we look for evidence of corporate culture which is, by nature, more financially conservative.

Paul Pfleiderer at Stanford likens corporate debt to eating potato chips, “you may be fine if you can commit to eating just a few chips. But if you can’t stick with that commitment, you might be better off if you hadn’t started eating them at all”.

We commend the work of the Stanford experts; as with all addictions, admitting you have one is the first step of recovery.

Andrew McNally is Chief Executive Officer of Equitile Investments Limited

*The Leverage Ratchet Effect Anat R. Admati Peter M. DeMarzo Martin F. Hellwig Paul Pfleiderer July 31, 2013