Loading...

5th August 2020

In 1981 Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers released their fourth album, Hard Promises. Given Petty’s earlier success his record label, MCA’s Backstreet Records, decided to put him in their so-called “superstar pricing” category and charge $1 more than the usual album price of $8.98. In today’s money, given US inflation since, the standard price would have been $25.75. Petty objected in the press and his cause became a popular one amongst music fans. He even considered renaming the album “Eight Ninety-Eight”, but in the end MCA backed down and the album was launched at the standard price of $8.98. Today, thirty-nine years later, you can still download the album for $8.90.

Hard Promises reached number five in the Billboard 200 album charts, a slot now held by hip-hop artist Post Malone. Malone’s album can be downloaded from Amazon’s online music store for $12.49 – half the inflation adjusted price of Petty’s. Most fans no longer download albums, however. For around $10 per month they can access all the music they like through streaming services.

In 1985, 60% of all records sold were on vinyl, the rest were mostly on compact cassette which were gaining popularity as the Sony Walkman demanded a portable format. By the time Petty released his next album four years later, just 5% of records were sold on vinyl, 51% were on cassettes and 40% were sold on CD (for those who remember rewinding cassettes with a pencil, the durability of a CD was a blessing). Today, 89% of music is listened to in digital form, either downloaded or via paid subscription streaming services.

For the music industry, managing these technological shifts has been tricky. Annual US recorded music sales peaked in 1999 at around $14 billion and are yet to reach that level again. As consumers switched from buying CD’s to digital downloads, they started buying single tracks rather than albums. As they switched from using iPods to smartphones, the industry found itself in direct competition with apps and games.

Although it has been tough for the music industry, however, its customers have never had it better. They can now access more music, at lower cost, with more convenience and have smarter ways to find the music they like.

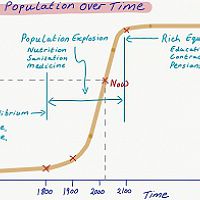

Buckminster Fuller, American architect and futurist, coined the term “Ephemeralization” – the ability, through technological advancement, to do “more and more with less and less until eventually you can do everything with nothing”. At an accelerating pace we can gather the same products and services with less time, effort and resources. The end-point of Fuller’s logic may seem fantastical but the process he describes, dematerialisation, not only has important implications for the environment (Fuller was an environmental activist), but also the inflation debate. Especially after COVID-19.

As it happened, Tom Petty’s 1981 fight against MCA’s proposed price hike marked an economic watershed. Interest rates had reached a post-war peak, just one year after inflation reached a thirty-three year high (see Slide 2 in accompanying Chart Book). Since that turning point, the direction of travel for both inflation and bond yields has, more-or-less, been one-way.

Inflation and interest rates were not the only economic metrics to peak at the time. Growth in the labour force topped out, as did the number of people working in manufacturing. US national debt reached its post-war low and federal tax revenues as a percentage of national debt reached an all-time high (Slide 3). On the trade front, although the US had been running a deficit since the mid-seventies, the pace of deterioration was now accelerating. Inflation, interest rates, debt, deficits, employment, and demographics were all at a turning point.

Politics and technology back then were poised to transform the global economy. Post-war economic orthodoxy was being upended by the Thatcher government and, soon to be elected, Ronald Reagan was about to change the established economic narrative on a grand scale. In addition, more fundamental phenomenon were bubbling under the surface; Poland’s “Solidarity” movement, for example, had recently been legitimised, setting the scene for the opening of Eastern Europe, and Tim Berners-Lee was already working on a technology (ENQUIRE), today seen as a precursor to the modern internet.

A new turning-point?

Now that inflation and long-term interest rates in the US are close to zero, have they reached a natural terminus? Are we poised to enter a more inflationary regime and will COVID-19 be the catalyst for that?

Financial markets are sending mixed signals. The gold price, a classic hedge against the devaluation of money, suggests inflation is coming, and quite soon (Slide 4). Breakeven inflation rates on the other hand, derived from differing yields on treasury bonds and index-linked treasuries, suggest a more sanguine attitude from markets (Slide 5).

There are four economic reasons why this forty-year inflation trend might reverse; Repression, monetisation, populism and economic nationalism. None of these, however, have been inflationary so far and, after COVID-19, there might be a more fundamental reason why they won’t.

Repression

In 1981, governments and central banks were determined to fight inflation, now they want it. As government debt has returned to extreme levels – US tax revenues are now only 7% of federal debt - they need to borrow at extremely low real interest rates (so-called financial repression) and have those borrowings eroded by inflation.

We’ve been in a financially repressive environment since the Global Financial Crisis, but it seems set to deepen even further. If inflation does exceed the Federal Reserve’s target, interest rates, they argued before COVID-19, should not be increased until the “lost inflation” in the preceding period of undershooting is “made up”. They have already decided that if inflation takes off, they will let it run.

Governments do not easily get what they want though, and engineering inflation is not always easy. The experience of the Great Inflation leading up to 1981 left us thinking inflation is normal - a mean to which the economy will naturally revert – but a longer look through history dispels that notion. The 1800s, for example, saw regular swings between inflation and deflation (Slide 6).

Monetisation

“Unconventional” monetary policy, initially used to secure the functioning of the financial system, has turned “conventional”. Central banks around the world continue to buy assets at unprecedented rates and the monetisation of government spending is now, implicitly at least, policy (Slide 7).

If Milton Friedman, was right that “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon” then this should be deeply concerning. We are witnessing one of the most startling monetary expansions in history.

There is most likely more to come though. Our CIO, George Cooper, has written a lot about the rise of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT), which principally argues that central banks can expand their balance sheets ad infinitum and governments can run significant deficits without adverse consequences. Although not openly admitted, MMT has been adopted in an accelerated fashion during the COVID-19 pandemic.

There is no direct line from QE to inflation though. QE does not necessarily drive money supply growth and money supply growth does not necessarily drive inflation. Both are pre-requisites for inflation but to take effect the velocity of money, the frequency with which supply is used to purchase goods and services, must also increase.

Although the money supply has been growing for some years, its velocity has been slowing. More acutely, as the supply of money has spiked during the COVID-19 crisis, its velocity has collapsed (Slide 8).

Populism

Economic populism has gone mainstream and policies are increasingly directed at addressing economic inequality. In contrast to the financial crisis response, when monetary policy favoured the asset rich, fiscal policy is increasingly directed towards middle and low-income families. Furlough payments, a growing array of incentives to restart the economy, and newly announced infrastructure projects are now couched as “levelling up”.

If they work, these policies should engender a higher propensity to spend and the velocity of money could turn at last.

Governments might find this more difficult than they think though. High income earners may well be the long-term beneficiaries of a structural shift to remote working and if unemployment does spike, which we think it will, unemployment payments are unlikely to be as generous as furlough payments.

In addition, many of the schemes designed to directly spur economic activity, such as incentives for dining out and buying bicycles, command headlines, but they are extremely small relative to the size of the economy. Similarly, infrastructure projects take a long time to start and their economic viability is often later called into question.

So far, empirically, the crisis hasn’t upended the economic pyramid. The cash deposits of the top 1% of wealth owners continue to grow while those of the bottom 90% have declined throughout the current crisis (Slide 9).

Economic nationalism

The opening of Eastern Europe and China unleashed a disinflationary force across the globe. With trade tariffs as a percentage of global trade now ticking up, this long-term dynamic might have changed.

Tariffs on traded goods, notwithstanding a recent uptick, have been in long term decline. The average global tariff rate fell from 8.5% in 1994 to 2.5% in 2017. Since mid-2018 that trend has started to reverse - in particular, with respect to goods traded between the US and China.

If we assume inflation is caused by factor constraints, then some retrenchment from globalisation should, theoretically, increase inflationary risk. If economies become more susceptible to national labour constraints, for example, then they should become more susceptible to upward cost pressure. Unlike in history, however, labour does not have the pricing power it once did - union membership in the US is close to 10% today, in 1981 it was more than 20% - and the rise of the “gig economy” reduces the ability of workers to collectively push for wage inflation.

Trade tariffs have always come and gone in the US. Washington himself imposed a 5% tariff on all imports and as Lincoln said, “Give us a protective tariff, and we shall have the greatest nation on earth”. New tariff regimes though are nearly always overturned later (Slide 10). The overall average tariff remains in long term decline. Regardless, it is not empirically clear that tariff increases are indeed inflationary for the US economy. On the assumption that any increase or decrease in tariffs would take some time to feed through to headline inflation numbers, we looked at the change in the total import tariffs as a percentage of total imports and compared that with average inflation rates in the ensuing three years. If anything, tariff cuts have generally been followed by periods of inflation (Slide 11).

What’s remotely possible?

Dematerialisation of the economy can be seen well beyond the music industry.

Based on a rough calculation the value of US GDP per pound of material rose from $3.64 in 1977 to $7.96 at the turn of the century. As a result of technological advances made since then, dematerialisation has accelerated; copper cables, newspapers, encyclopedias, maps, cameras, camcorders, yellow pages, VCRs, landline telephones, calendars, clocks, calculators, travel agents – all have disappeared or are disappearing fast. The list goes on and it’s growing - as tablets and smartphones develop, for example, the long-term prospects for the PC and the laptop computer are not looking good.

COVID-19 might well have unleashed a much bigger wave of dematerialisation through remote working. Dematerialised corporate meetings, sales pitches, employee reviews, staff training and so on will need less planes, fewer trains, and less physical office space to make them happen. Business cards, reception desks, desk-phones, water-coolers, staff canteens will all become less necessary.

According to a March 2020 post by the Pew Research Center, 37% of U.S. private industry workers and 4% of state and local government workers had a flexible workplace prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Now 98% of people surveyed say they would like to work remotely, at least some of the time, for the rest of their careers. At the same time, PwC’s recent survey of 120 U.S. companies found that 55% of executives plan to offer remote work at least one day a week after COVID-19 is behind us - up from 39% pre-pandemic. A recent Reuters analysis of earnings calls revealed that more than 25 large companies in the US plan to reduce their office space of the next year.

Announcements are already being made to this effect. Japan’s Fujitsu recently said that it would halve its office space in three years as it rewrites the way employees work. The IT solutions company said it hopes to have its 80,000 employees work flexible hours and from home wherever possible. Siemens have made similar comments saying that they will “establish mobile working as a core component of its ‘new normal’ and will make it a permanent standard, both during the global pandemic and beyond”.

At the risk of sounding extreme, office blocks are about to be dematerialised along with iPods and cameras.

The impact on company costs will be large and, if competition holds, deflationary forces should ensue. Moreover, the “dematerialized” parts of the economy will be the parts that have been the most inflationary in recent years - not just commercial property but also professional services, education and even medical care (Slide 12).

Dematerialisation affects the inflation equation in some subtle ways too. The average launch price of each new generation of iPhone, for example, has been increasing for some years but this is not reflected in official inflation numbers dollar for dollar. The so-called Hedonic Adjustment, used by statistical agencies to take account of the improved quality and functionality of products, adjusts prices downwards as products improve. The validity of this is questionable (see Hedonism and the value of money by our CIO, George Cooper) but the long-term consequences for inflation are intriguing. As technology “dematerializes” the economy, the price and volumes sold of “dematerialized” products and services falls, depressing the rate of inflation and nominal GDP. At the same time, the hedonic adjustment of the technology price depresses the published inflation rate even further.

In aggregate, the more dematerialisation there is, the more difficult it will be for headline inflation to rise. The more our economic life is digitized, the more hedonic adjustments apply, the harder it will be for central banks to report inflation.

Investment implications

Once COVID-19 has passed, the inflation outlook is one of distinctly opposing forces. Although there are few signs of an inflationary impact so far, monetary expansion, along with some redistributive economic policy and economic nationalism, does present an inflationary threat. On the other hand, the switch to remote working could bring the next leg of dematerialisation, a powerful deflationary force.

From an investment point of view this presents an interesting challenge.

Inflation is good for equity and property investors, and bad for bond holders. Conversely, deflation is bad for equities and good for holders of cash and bonds.

Inflation wasn’t good for equities during the 1970’s when their value failed to increase in real terms. Inflation in the 1970’s, however, was not only monetary (although this was a period of financial repression) but also a consequence of cost pressures stemming from the oil crises of 1973, significant wage inflation, and declining productivity (probably the worst environment for corporate earnings one could construct). With accelerated dematerialisation after COVID-19, such cost pressures are unlikely going forward (Slide 13).

Deflation is generally seen as bad for equities, it’s normally accompanied by slow or negative growth and a debt-deflationary cycle can persist for much longer than a normal economic cycle. Deflation caused by a rapid period of dematerialisation, however, naturally leads to a two-tier market. In simple terms, those being dematerialised – in this case commercial property – do badly. Those enabling the dematerialisation do well – in this case any service or product provider that supports remote working.

Finally, there is an irony. The bent of central bankers is such that, the more the deflationary force of dematerialisation takes hold, the greater the incentive for them to do more of what they’ve done so far. For equities overall, this a good thing. For equities on the right side of dematerialisation, with no hard promises, this is ideal.

Why ownership matters more than ever

2

Why ownership matters more than ever

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

Debtonator - How Equity Can Work for All of US

2

Debtonator - How Equity Can Work for All of US

2

Can fair fees make active managers more sustainable?

2

Can fair fees make active managers more sustainable?

2

John Authers of the Financial Times in conversation with George

2

John Authers of the Financial Times in conversation with George

2

An interview with World Finance

2

An interview with World Finance

2

Debt & the magical mathematics of Brahmagupta

2

Debt & the magical mathematics of Brahmagupta

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Is it time to rethink monetary policy?

2

Is it time to rethink monetary policy?

2

Modern Monetary Theory - The Magic Money Tree

2

Modern Monetary Theory - The Magic Money Tree

2

Meerkats and Market Behaviour - Thoughts on October's stock market fall

2

Meerkats and Market Behaviour - Thoughts on October's stock market fall

2

0

0

Money, Blood and Revolution

2

Money, Blood and Revolution

2

Seductive Charm

2

Seductive Charm

2

Bloomberg Radio - Equitile’s Cooper: How to Fix Economics

2

Bloomberg Radio - Equitile’s Cooper: How to Fix Economics

2

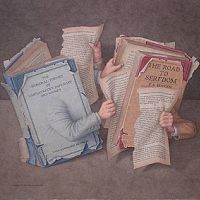

Books

1

Books

1

The unspoken political truth about debt

2

The unspoken political truth about debt

2

Stock market superstars and the danger of a buy-and-hold investment strategy

2

Stock market superstars and the danger of a buy-and-hold investment strategy

2

Build a company on prudence and trust, not debt

2

Build a company on prudence and trust, not debt

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Regulating Psychopaths

2

Regulating Psychopaths

2

Lumbering corporate dinosaurs face mass extinction

2

Lumbering corporate dinosaurs face mass extinction

2

Captain Kirk and the science of economics

2

Captain Kirk and the science of economics

2

Still Flashing Green: Equities in a world of higher growth and financial repression

2

Still Flashing Green: Equities in a world of higher growth and financial repression

2

Invest in Resilience

1

Invest in Resilience

1

A creditable recovery

2

A creditable recovery

2

Is corporate debt addictive?

2

Is corporate debt addictive?

2

Facts not Opinions

2

Facts not Opinions

2

Norway Moves to America - Mean reversion and industrial revolutions

2

Norway Moves to America - Mean reversion and industrial revolutions

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

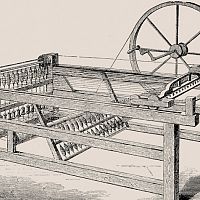

Luddites and the New Social Revolution

2

Luddites and the New Social Revolution

2

Undoing the Mistakes of QE

2

Undoing the Mistakes of QE

2

Crisis Economics

2

Crisis Economics

2

The Consequences of COVID-19

2

The Consequences of COVID-19

2

Monetary Policy on a War Footing

2

Monetary Policy on a War Footing

2

Hanging the Wrong Contract?

2

Hanging the Wrong Contract?

2

Reckless Prudence - How to break a pension system

2

Reckless Prudence - How to break a pension system

2

In Search of Stability & Growth - If only Europe was more like the US

2

In Search of Stability & Growth - If only Europe was more like the US

2

Investment Letter - Eternal Adaptation

2

Investment Letter - Eternal Adaptation

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

While Stocks Last - Reflections on the share buyback debate

2

While Stocks Last - Reflections on the share buyback debate

2

Over Easy - Can Monetary Policy Become Self-Defeating?

2

Over Easy - Can Monetary Policy Become Self-Defeating?

2

George Cooper Talks to Bloomberg Radio - Time to Brexit-proof Investment Funds

2

George Cooper Talks to Bloomberg Radio - Time to Brexit-proof Investment Funds

2

George Cooper Talks to Bloomberg Radio - Central Bankers Are Irresponsible

2

George Cooper Talks to Bloomberg Radio - Central Bankers Are Irresponsible

2

Revolutionary Fervour

2

Revolutionary Fervour

2

The Lost Shield? - The small print in Trump's tax plan

2

The Lost Shield? - The small print in Trump's tax plan

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

The Origin of Financial Crises

2

The Origin of Financial Crises

2

'Fixing Economics' by George Cooper: Book Review

2

'Fixing Economics' by George Cooper: Book Review

2

COVID-19: Our initial response and thoughts

2

COVID-19: Our initial response and thoughts

2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2