Loading...

20th December 2019

A political earthquake hit the UK last week, the tremors from which will go on for years. Carpet fitters from Grimsby joined forces with bankers from Beaconsfield to deliver the biggest Conservative majority since the 1980’s. To get there, the Conservative Party has been through somewhat of a revolution. By being counter-cultural on the one hand with a right-leaning social agenda, and by deserting its own economic history on the other with a left-leaning economic agenda, the oldest political party in the world turned on a sixpence to win over the electorate.

It not only potentially marks the start of a new political settlement, in the UK and elsewhere, but perhaps even the end of political turmoil which has come to define the last five years.

We are now approaching five years since we established Equitile Investments and four years since we launched the Resilience Fund. The Conservative revolution is not, of course, the first political revolution we’ve had in that time. The election of a property tycoon, standing on an overtly nationalistic platform, to the White House (itself preceded by the vote for Brexit) up-ended the political, economic and social consensus which had gone practically unchallenged for decades.

In many ways, this shift comes as no surprise. The books and papers behind our investment philosophy, some of which I’ve linked to here, pointed to imbalances in the economic and political system which pre-disposed it to disruptive change. Equally, our investment approach was designed from the very start to deal with that change.

While political revolutions have dominated the headlines there’s been another one bubbling in the background. An economic revolution, driven by the exponential development of new technologies - and their convergence on industries previously beyond technological reach - is making us more productive at a rate few people can perceive.

When we formed Equitile, for example, the fastest micro-chip in the world had six million transistors - the fastest today has more than thirty million. Those familiar with Moore’s Law will know this has a profound impact on the speed and cost of computing power. Moreover, deployment of that power in new areas is leading to revolutions all over. The cost of mapping the human genome, for example, has fallen by more than 85% in just five years and so the number of patents filed for gene-based therapies has grown exponentially.

Who would have thought that, while the anxiety machine of the media wrestled with the drivers of political turmoil, the world economy would be 20% bigger today than it was five years ago? In the time that we have been in business, the world has added another economy the same size as that of the US.

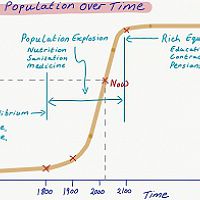

Moreover, as that growth has mainly been in less developed economies, another 600m people have been brought into the middle class. In fact, since we started Equitile the middle classes and rich, according to OECD definitions, now collectively make-up more than fifty percent of the global population. While developed countries are seeing political shifts in response to a perceived unfair share of the economic pie, the global economic pie is being shared more equally.

It’s nearly six years since I read a book review in the Economist which, in many ways, marked the birth of Equitile.

The book in question was Money, Blood and Revolution by our very own, Chief Investment Officer, George Cooper. It was a clear expose of the fundamental flaws in mainstream economics. Drawing on the history of paradigm shifts in other sciences, the book offered a framework for understanding how economics, in its current incarnation, will ultimately be overturned.

At the heart of George’s thesis was a different understanding of human nature. In practice, we are not the independent rational optimisers, so-called homo economicus, which are the subject of most economic models. The truth is, we have failed to escape our Darwinian heritage – we are still driven by the behaviour we originally aquired to compete for scarce resources. It is in our nature to compete with one another and, importantly, to judge our successes against one another.

It’s a take on human nature that more readily fits the evidence; why else would someone spend £2,000 on a Louis Vuitton suitcase when the same “utility” can be had from one that comes at a tenth of the price. It’s the side of human nature behind that well-known Gore Vidal quote “When a friend succeeds, a little something in me dies.”

These Darwinian forces, however, are not as dark as they appear on the face of it. It’s the human need to compete, compare and follow one another that keeps us striving to get better; to work and to innovate; at a deeper level, to collaborate and to trust. It is the ultimate force behind economic progress itself and so offers a much more optimistic backdrop than that offered by the mainstream of the dismal science. Animal spirits, as Keynes called them, play no role in modern financial theory but it is those spirits that drive us inexorably forward.

It’s this understanding that leaves us fundamentally optimistic from an investment point of view and explains why, despite the political backdrop, the global economy has continued to perform as well as it has.

The Economist’s review of George’s book had a catchy title - Revolutionary Fervour. With hindsight, the Revolutionary part of the title was apt. Although the review’s author was referring to George’s use of Thomas Kuhn’s Theory of Scientific Revolutions to guide his thinking, revolutions in thought have, in the end, been behind the political, technological and economic revolutions we have seen during our first few years.

Just before the publication of the Economist review, I wrote an article for the Financial Times arguing that the propensity for central banks to keep their economies growing by pushing ever-more debt into the system was destabilising. Not just in the way that we saw in the Global Financial Crisis but because it facilitated a land-grab for productive assets, largely public equity, by just a few – a key factor behind political disgruntlement we’ve seen since. Moreover, central banks’ collective response to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 was, and still is, to do even more of the things that led to that crisis in the first place – accentuating the wealth polarising forces as I later explained in my own book, Debtonator.

If intellectual revolutions lead to real world revolutions, in monetary circles it’s the other way around. It is the bent of central bankers to seek out the intellectual framework which supports what they need to do anyway. As George wrote before the 2008 crash, the Origin of Financial Crises are the central banks themselves and so they are motivated to solve them at any cost.

Growing support for so-called Modern Monetary Theory is a case in point. Just as Quantitative Easing has started to lose its potency, the need for fiscal expansion in the western world necessitates the monetisation of government debt. MMT offers an intellectual framework to support this and so it is naturally garnering support in central banking circles[i].

Regardless of whether Modern Monetary Theory becomes fully ingrained in central banks’ thinking, the direction of travel is clear. Despite the inherent flaws in monetary dogma, monetary policy will remain extremely supportive for a very long time yet.

As Boris Johnson’s Conservatives tack left on economics, they’ll become more sanguine on the Bank of England’s inexorable drift away from its foundational mission of providing a stable monetary base. Instead, they’ll come to accept, one way or another, that central bank monetisation of government spending is the right approach. In time, they’ll embrace some form of Modern Monetary Theory, despite its inherent flaws. Trump of course has already gone further in this respect, haranguing the Federal Reserve to lower rates and expand its balance sheet aggressively[ii]

From an investment point of view this removes a significant risk.

Excessive wealth disparity pre-disposes electorates to finding socialism attractive. As George wrote in the Tale of Two Walls, the first response to workers’ reduced share of the economic pie was nationalistic – the second could as easily be Socialistic. The Conservative’s revolution might just be a harbinger of a political trend that mitigates this threat.

The threat to economic and political stability, I wrote about in Debtonator, remain inherent to the system. Inherent risks, however, are not immediate risks and following the political revolution we now witness, they are likely to remain benign for decades.

The Equitile Resilience Fund is approaching its fourth anniversary. Uncertainty is ever-present[iii] but the dynamics as we see them today are even more favourable for the global equity markets than they were when we launched the Fund.

The technological revolution has a long way to run - by this time next year the fastest micro-chip will have fifty million transistors not thirty and another one hundred million people would have turned middle class. Despite the headlines, we will be making more, selling more and buying more; we will become more innovative, more collaborative and more productive. Returns on capital will continue to rise.

In the meantime, central banks will remain dovish for a very long time to come. Not only do they have no choice at this stage, they are creating the intellectual framework to support their actions and the new political settlement will support them.

It would be wrong of us to become complacent though. The day we launched the Resilience Fund we wrote a Letter to our new investors explaining our approach. We called it Eternal Adaptation, taken from the mission statement of one of our first investee companies, “Change is an immutable law; eternal adaptation is the price of survival”. We took the advice to heart and no longer own shares in that company but the philosophy stays with us and we remain as alert to the revolutions to come as we were through the ones we’ve just seen.

The full collection of essays can be found on our website. To subscribe for updates email insights@equitile.com

[i] Similarly, there’s increasing talk of interest rate policy makers adopting a so-called make up strategy which not only accounts for current inflation shortfalls but also the lost ground from previous shortfalls.

[ii] This is within a Republican Party which not too many years back was heavily influenced by the Tea Party who had stable money as a cornerstone of their thinking.

[iii] See Tales of an Astronaut – Lessons from the Unknown

Norway Moves to America - Mean reversion and industrial revolutions

2

Norway Moves to America - Mean reversion and industrial revolutions

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

Facts not Opinions

2

Facts not Opinions

2

Brochure

1

Brochure

1

Debtonator - How Equity Can Work for All of US

2

Debtonator - How Equity Can Work for All of US

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

Captain Kirk and the science of economics

2

Captain Kirk and the science of economics

2

The Lost Shield? - The small print in Trump's tax plan

2

The Lost Shield? - The small print in Trump's tax plan

2

Modern Monetary Theory - The Magic Money Tree

2

Modern Monetary Theory - The Magic Money Tree

2

Build a company on prudence and trust, not debt

2

Build a company on prudence and trust, not debt

2

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

A creditable recovery

2

A creditable recovery

2

Over Easy - Can Monetary Policy Become Self-Defeating?

2

Over Easy - Can Monetary Policy Become Self-Defeating?

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

In Search of Stability & Growth - If only Europe was more like the US

2

In Search of Stability & Growth - If only Europe was more like the US

2

Invest in Resilience

1

Invest in Resilience

1

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Reckless Prudence - How to break a pension system

2

Reckless Prudence - How to break a pension system

2

The Origin of Financial Crises

2

The Origin of Financial Crises

2

While Stocks Last - Reflections on the share buyback debate

2

While Stocks Last - Reflections on the share buyback debate

2

Meerkats and Market Behaviour - Thoughts on October's stock market fall

2

Meerkats and Market Behaviour - Thoughts on October's stock market fall

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

Monetary Policy on a War Footing

2

Monetary Policy on a War Footing

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

Crisis Economics

2

Crisis Economics

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Investment Letter - Eternal Adaptation

2

Investment Letter - Eternal Adaptation

2

Money, Blood and Revolution

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2

Money, Blood and Revolution

2

Register for Updates

12345678

-2