Loading...

27th October 2020

“Suppose an individual believes something with his whole heart; suppose further that he has commitment to this belief, that he has taken irrevocable actions because of it; finally, suppose that he is presented with evidence, unequivocal and undeniable evidence, that his belief is wrong: What will happen?

The individual will frequently emerge, not only unshaken, but even more convinced of the truth of his beliefs than ever before. Indeed, he may even show a new fervour about convincing and converting other people to his view.”

- Leon Festinger, 1956 -

The stock market will crash on December 21st.

The stock market will crash on December 21st.

In the few seconds it took you to read that first sentence your innate survival instincts will have kicked in. They are telling you: something bad is going to happen, you need to act. The rational part of your brain is pushing back, saying: nonsense, he has no idea what will happen to the stock market on December 21st. But you still have that nagging worry.

Grabbing peoples’ attention and coercing them into action with scary stories and doomsday prophecies is an old trick. It exploits our risk aversion bias, which is part of our survival instincts telling us to look out for danger. The scary story trick is ubiquitous, journalists use it, religions use it, campaign groups use it and of course governments use it. Learning when to ignore scary stories and when to see through them is an important life skill, and for investors an essential skill.

In 1955, a small team of social scientists conducted a remarkable piece of covert research which taught us a lot about how we respond to scary stories. The scientists infiltrated a doomsday cult and were able to observe, at first hand, how the beliefs and behaviours of the cult members evolved, over time, in response to a series of failed prophecies.

The central doomsday prophecy of the cult was that a huge flood, starting from Great Lake on December 21st, would sweep down through North America. The members believed they were part of a select few who had been chosen, by spacemen from the planet Clarion, to be warned of and saved from the impending apocalypse. They believed the spacemen would reward them for their faith by transporting them, in flying saucers, to safety on alien planets.

Leon Festinger and his team of observers joined the cult in early November, in time to see the cult members preparing for their rescue prior to the flood.

In the run up to the flood the cult leaders prophesised a series of flying saucer landings: “the believers thought that they would be rescued before the cataclysm took place. They expected flying saucers to land, pick up the chosen ones, and transport them to either other planets or to some safe places designated by the Guardians.”

The first prophesised collection was scheduled for 4pm On December 17th. The cult members were told to wait for the arrival of the flying saucers in the back yard of the cult’s headquarters. They were told to remove any metal objects from their clothing as these would heat up during the space flight causing nasty burns. Having taken this sensible precaution, the group duly waited for the space craft to arrive. 4pm came and went without sight of the flying saucers. The prophecy had been precise in timing and location and so its failure was incontrovertible. Festinger and his team then recorded how the group responded to the disconfirmation of their failed prophecy. After a few hours of discussion, the group convinced themselves their spacemen masters had planned the events as a practice run and the flying saucers were going to arrive at another time. This invented explanation did not just allow the group to retain their beliefs, perversely it appeared to have strengthened their conviction. Festinger and his team observed this pattern many times.

Shortly after the flying saucers failed to arrive, an inquisitive teenager turned up at the cult’s house. The cult had become quite famous and was attracting attention of numerous journalists, television reporters and other curious individuals. Without a shred of supporting evidence, and despite the teenager’s protestations to the contrary, the group decided he had been sent by the spacemen with instructions for the group. His inability or refusal to deliver the instructions was taken as a test of their faith – obviously!

The upshot of the December 17th event was that the real disconfirmatory evidence – the absence of flying saucers – was ignored while confirmatory evidence – the teenage messenger – was invented. It was an extreme example of selection bias and confirmation bias, where any inconvenient data is discarded.

Shortly after the first failed prophecy, the group’s leader announced that the flying saucers had just been delayed and would arrive later that night. Again, the group waited outside the house, this time into the small hours of the morning, and again nothing happened. This time the group coped with the disappointment by simply ignoring it. They waited in the back yard into the early hours of the morning, through a long cold night, for the flying saucers to arrive, and when they did not, just returned to the house without discussion.

Following these two disconfirmations Festinger’s team noted an interesting change in the group’s behaviour toward outsiders: “no longer were they indifferent or preoccupied with other matters. Rather they made pointed and deliberate attempts to persuade and convince.” In response to being proven wrong, the group did not change their beliefs, rather they stepped up their proselytising efforts, actively engaging with outsiders in an attempt to win new converts. “The need for social support following the disconfirmation on Friday was very strong.”

After the failed prophecies one of the cult leaders explained his continued faith in the cult to one of the undercover observers: “I’ve had to go a long way. I’ve given up just about everything. I’ve cut every tie: I’ve burned every bridge. I’ve turned my back on the world. I cannot afford to doubt. I have to believe.” The leader felt he had to keep the faith because to do so would require recognising the huge cost of previous mistakes. The loss to his status and damage to his ego were too much to contemplate. We now call this type of flawed thinking a sunk cost fallacy. The sunk cost fallacy is a devastating behavioural problem able to permanently lock people into bad decisions. The greater the sunk cost, either financially or reputationally, the more difficult it is to acknowledge the mistake and correct it.

After many no-shows by the flying saucers, the much-anticipated, December 21st doomsday arrived, and the group waited patiently for the flood to start. Once again, the day passed without incident and, once again, the group ignored the data and set about the torturous process of explaining away their failed prophecy.

The December 21st flood prophecy was the principal belief of the whole cult so its disconfirmation was a serious blow to the members. The lack of a flood required an especially clever story. The explanation they settled on was an ingenious logical contortion: the spacemen had decided to save the world from the flood as a reward for the cult’s faith. The flood did not happen because they believed it would happen. The logic was entirely circular but, to the cult members, it provided the confirmatory narrative they required.

Rather than being beaten down by the failed prophecy the group emerged jubilant with their faith further reinforced. In Festinger’s words, “they had a satisfying explanation of the disconfirmation…From this point on their behaviour toward the newspapers showed an almost violent contrast to what it had been. Instead of avoiding newspaper reporters and feeling the attention they were getting in the press was painful, they almost instantly became avid seekers of publicity.”

As an interesting aside, the researchers also noted that cult members who remained living within the main group after the December 21st disconfirmation tended to emerge from the experience with their faith preserved or enhanced. On the other hand, those who had to cope with their disappointment alone tended to lose their faith. Social confirmation, groupthink and peer-pressure were important parts of preserving and reinforcing the members beliefs.

Festinger’s story provides some useful hints for how to spot and when to ignore false doomsday prophecies.

Are those making the doomsday story heavily invested in it? Does the rationalisation of the scary story keep changing? Do the proponents have a substantial financial or reputational sunk-cost making, it impossible to admit they may be wrong? Is contradictory, positive, data being ignored? Is supportive, negative, data being manufactured? Are the protagonists listening only to those who share their own views? Are the protagonists evangelical in their beliefs, needing to proselytise their beliefs?

If you see these behaviours, you should probably nod politely, ignore the story, and move on. Most likely it is nothing more than an attempt to grab your attention and control your behaviour with scaremongering. Do not waste time trying to convince them with science, a true believer will have too much of their reputation invested in the story to listen to reason.

We will leave it to you to judge if Festinger’s findings have any relevance to current events.

As for that prophecy of a stock market crash on December 21st – ignore it. We, like everyone else, have no idea what will happen to the stock market that day. But, if it does crash we will claim vindication and republish this article, if it does not we will tell ourselves the crash was avoided because people heeded our warning and adjusted their portfolios ahead of time.

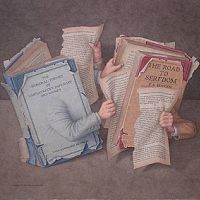

The full story of the doomsday cult was published in 1956 by Leon Festinger and his colleagues in ‘When Prophecy Fails’ it makes excellent reading. For the benefit of our Welsh readers, who are being told it is too dangerous to buy books from shops, we have included the link to the book’s Amazon page.

If you would like to join our mailing list please send a message to info@Equitile.com

A creditable recovery

2

A creditable recovery

2

No Hard Promises - thoughts on inflation after COVID-19

2

No Hard Promises - thoughts on inflation after COVID-19

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

An Impossible Trinity?

2

Luddites and the New Social Revolution

2

Luddites and the New Social Revolution

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

The Anxiety Machine - The end of the world isn't nigh

2

Lockdown: What did we get? Why did we do it?

2

Lockdown: What did we get? Why did we do it?

2

Investment Letter - Eternal Adaptation

2

Investment Letter - Eternal Adaptation

2

'Fixing Economics' by George Cooper: Book Review

2

'Fixing Economics' by George Cooper: Book Review

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

Investment Letter - Constant Reformation

2

The Consequences of COVID-19

2

The Consequences of COVID-19

2

Reckless Prudence - How to break a pension system

2

Reckless Prudence - How to break a pension system

2

Captain Kirk and the science of economics

2

Captain Kirk and the science of economics

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part I

2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Tales of an Astronaut - Lessons from the Unknown

2

Meerkats and Market Behaviour - Thoughts on October's stock market fall

2

Meerkats and Market Behaviour - Thoughts on October's stock market fall

2

Is corporate debt addictive?

2

Is corporate debt addictive?

2

Facts not Opinions

2

Facts not Opinions

2

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

2016: A Tale of Two Walls

2

Crisis Economics

2

Crisis Economics

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

Depressed lobsters and the dividend yield trap

2

Modern Monetary Theory - The Magic Money Tree

2

Modern Monetary Theory - The Magic Money Tree

2

Build a company on prudence and trust, not debt

2

Build a company on prudence and trust, not debt

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

Hedonism and the value of money - Part II

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

A New Maestro? Observations on an important speech by Fed Chairman Powell

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

Revival of the Fittest

2

In Search of Stability & Growth - If only Europe was more like the US

2

In Search of Stability & Growth - If only Europe was more like the US

2

0

Register for Updates

12345678

-2

0

Register for Updates

12345678

-2