Loading...

6th July 2020

As pubs and restaurants opened in the UK last weekend, we’ve heard mixed reports on how many customers returned. Either way, it doesn’t look like there was a mad rush back.

Most likely, they’ll see a repeat of the retail sector’s experience over the three weeks after they were allowed to open - things have picked up but not by much. Data from Springboard shows footfall in the high street is still less than 40% of what it was at the beginning of March. Retail parks are faring better but are still only seeing around 70% of the footfall they were before lockdown.

In George’s recent COVID-19 Insights piece he talked about the likely bifurcation in the fortunes of the very large companies and small ones, particularly in retail, hospitality and travel. It seems that his projection is playing out.

The Bank of England reported last week that, while SME’s had increased their net borrowing in May by £18.2 billion, large ones had paid off £12.9 billion of debt.

A recent ONS survey analysing the impact of COVID-19 paints a similar picture with the financial resilience of many small companies now being seriously tested. Of the 5,600 or so companies which responded, 14% were still not trading by mid-June. Of the 86% that were trading, 18% of their staff were still furloughed.

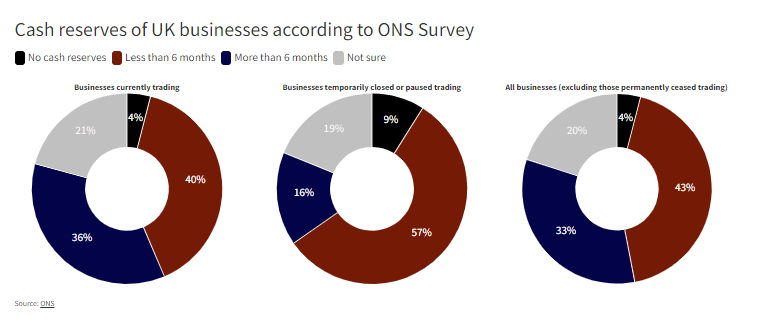

More worrying was companies’ assessment of their financial resilience. Of those businesses actually trading in mid-June, 44% said they have cash reserves to last less than six months. Including business that were still closed, close to half said they can’t survive more than six months given their current cash reserves.

The economy needs to pick up much more quickly if many of the UK’s smaller enterprises are to survive.

2nd December 2019

A visit to Tiffany’s would, to most of us, prove an expensive affair but the breakfast Antonio Belloni, Group Managing Director at LVMH, had with Tiffany’s CEO early in October will be the most lucrative one he’ll have this year. The European luxury conglomerate will overtake Switzerland’s Richemont as the leading player in high-end jewellery after it completes a EUR 14.6 billion takeover of Tiffany in 2020 – building on its position as global leader when it comes to fashion & leather goods, fine spirits and luxury boutique hotels.

The deal becomes most interesting, however, when one looks at the funding of it.

LVMH will acquire Tiffany by issuing corporate bonds at ultra-low rates. With their current 2024 bond yielding minus 12bps, the opportunity for the company to lock in long-term funding costs of close to zero is clear. Even bonds issued by LVMH with a 10 or 15 year maturities will yield next to nothing. Despite the low yield, they won’t struggle to find demand however - the company issued a EUR 300 million tranche with a negative yield in March this year and the deal was six times oversubscribed.

Even if longer-term funding costs were, say, 50bps - realistic in a world where USD 10 trillion of debt has negative yields and the combined entity will still only have net debt/EBITDA of 1.6x – LVMH will pay EUR 73 million annually to bondholders in return for Tiffany’s annual estimated operational cash flow of EUR 500-600 million.

In effect, the bondholders who are paying for Tiffany are bound to lose money, in real terms, while the shareholders of LVMH will extract a net annual cashflow EUR 430-530 million. And that’s before the growth - there are already material plans to expand in China and Japan, markets where LVMH has proven success (Tiffany has remained largely an American brand).

LVMH’s customers, of course, are the sort of people who own shares in LVMH. As central banks keep interest rates close to zero, assets like Tiffany can be bought at virtually no cost to the acquirer’s shareholders who, in turn, have more to spend on expensive handbags and jewellery.

It’s a textbook case of how wealth polarization works in practice in the current monetary environment. As an investor, in this case at least, it’s a chance to be on the right side of it.