Loading...

4th February 2022

The spectre of inflation has spooked stock markets since the end of last year with headline rates in the US for example above 7% – the highest since 1982. The Bank of England this week suggested that the UK will see a similar rate by April.

There are clear reasons why this inflationary impulse has occurred. Central banks around the world have supported a significant increase in deficit spending through the purchase of government debt and so we have witnessed the biggest Keynesian stimulus since World War Two. The Federal Reserve has more than doubled the size of its balance sheet since the outbreak of COVID-19. Moreover, this massive monetary expansion has been accompanied, for the first time in history, by government policies to shut down large sectors of the economy and impose working practices that have made it impossible for businesses to function as normal.

The outcome has been supply-chain disruption such as we have never seen which, as economies have opened, has led to both price and wage pressure throughout the system. Commodity and basic materials have seen prices up 20-80% from their lows and wages in some sectors, especially hospitality, have been rising at more than 10% p.a.

There are signs that some of this pressure may be about to ease. Industrial production is stabilizing back to pre-pandemic levels, shipping rates are now collapsing, and basic material prices are rolling over (except oil and gas). There are also signs that wage pressure isn’t compounding quite as much as feared as labour participation rates pick up.

We wouldn’t want to get too confident on the inflation front but if it is close to a peak, what would this mean for investors?

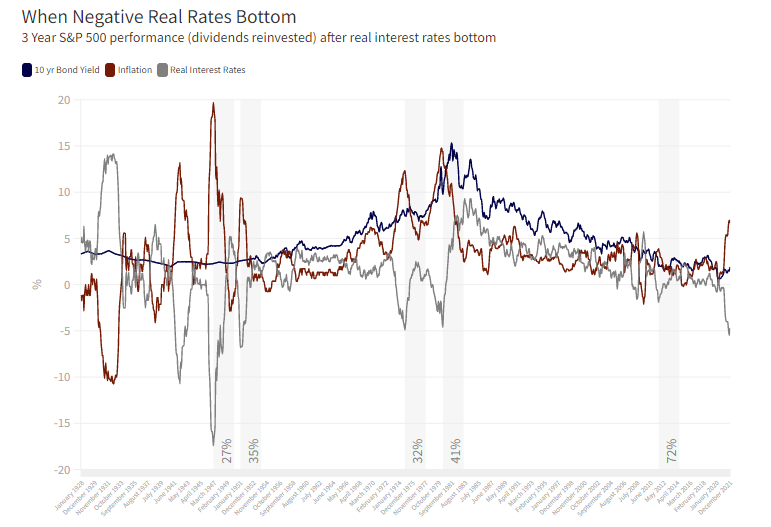

Although several interest rate hikes from the Federal Reserve are now priced in and bond yields have moved up this year, we still face the most negative real (inflation adjusted) yields since the 1970s.

Looking through a long lens in this chart going back to 1928, when negative yields have reversed it’s been because inflation has fallen sharply, not because bond yields have risen.

Once that reversal happens and real negative yields bottom out, it’s generally been a good time to buy the stock market with a long-term view. The grey bars on the chart show the ensuing 3 years market performance from the month that real rates turn.

29th June 2021

We have written a great deal over the last few years on the wealth polarising effect of monetisation. Given the significant increase in the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet through the COVID19 lockdowns, therefore, it should come as no surprise that the portion of net worth owned by America’s wealthy has increased again – nearly a third of all net worth in the US is in the hands of the Top 1% (see figure 1).

The most often cited cause of this is the Fed’s impact (although they largely deny this) on the price of assets held mainly by the well-off. There are, however, more subtle drivers too. The swings seen in asset markets, due to both COVID in 2020, and the longer-term effect rising leverage has on market volatility, has made it more difficult for the less-well off to hold on. In a bear market, as John Pierpont Morgan somewhat cynically pointed out, “stocks return to their rightful owners” and so if bear markets come more often and more sharply, then the rate of repatriation will only accelerate.

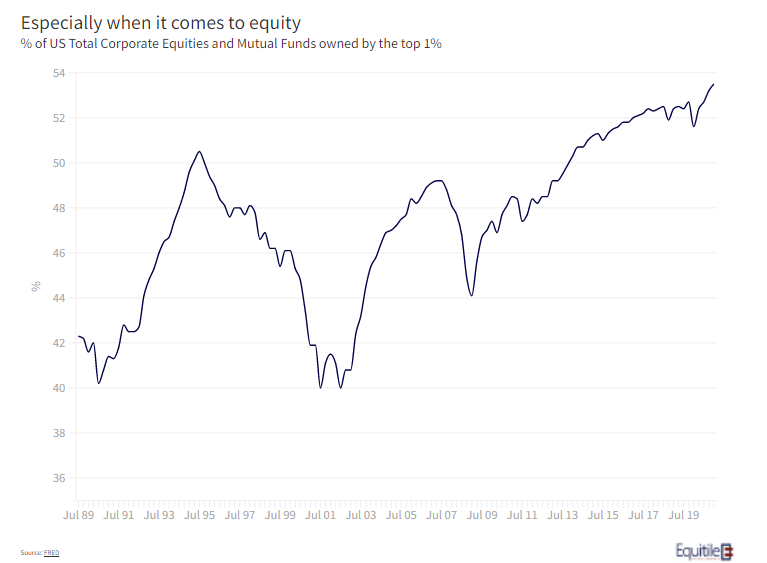

This might explain why, as shown in figure 2, the ownership of corporate equities and mutual funds in the US has become even more concentrated than for other forms of wealth. More than a half of all business equity, held either directly or indirectly, is held by the top one per cent of all owners. A trend that looks set to accelerate.

It may not only come down to the capacity to sustain losses, however. As in all western countries, good advice comes at a price. At Equitile we are not financial advisers but we talk to many advisers through the course of our business. As we see it, the crucial value of a good adviser is support and encouragement when the market has a set-back. A good adviser is in the best position to help investors overcome their natural behavioural aversion to loss, and to help plan their broader finances to make this easier. With good personal advice now scarce and expensive for those of lesser means, the ability to sustain losses floats ever upwards.

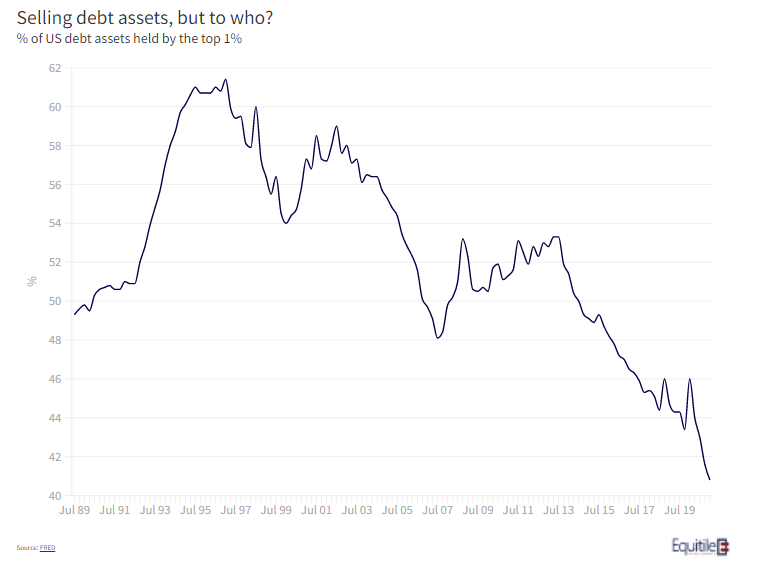

One intriguing move by the top 1% is their move away from bonds. Their holdings of debt assets (figure 3) has fallen from more than 60% to 40% of all debt assets in the last two decade - they sold aggressively throughout the COVID crisis.

With real interest rates in the US the most negative since the 1970’s, the potential for capital destruction through financial repression, for bond holders at least, is rising sharply. Perhaps the top 1% know this instinctively, or perhaps they are just better advised.